It started as a prank: a check for $700,008.50 and an order form requesting one Harrier Jet, mailed straight to Pepsi’s promotions department.

But this wasn’t a joke. The check was from a business student who believed Pepsi had made him a legally binding offer on national TV.

The dispute became a legal saga and a fixture in marketing classes, but it’s only one chapter in a larger story. Promotions have a way of misfiring when audiences take them literally, interpret them creatively, or simply follow the math where it leads.

Across industries, brands have learned this lesson the hard way. Hoover, McDonald’s, Red Lobster, and American Airlines all launched offers that looked clever on paper and then spiraled under real-world behavior.

Together, these five cases show how quickly a well-intended idea can tilt out of balance when assumptions, guardrails, or basic projections fall short.

The Pepsi Harrier Jet Misfire

Some marketing misfires read like sitcom setups … like the Pepsi Points Harrier Jet promotion.

In 1996, Pepsi launched its “Pepsi Stuff” loyalty program, inviting customers to trade points for branded gear. One commercial pushed the joke further, showing a teenager touching down at school in a Harrier II jump jet, complete with the caption “Harrier Fighter, 7,000,000 Pepsi Points.”

It was meant as playful exaggeration, the kind of reward no one was supposed to take literally.

Pepsi’s rules included one seemingly small detail: Customers could buy extra points for ten cents each. John Leonard, a business student who did the math, realized the math penciled out to roughly $700,000. He raised the funds, sent in the required fifteen physical points, and mailed Pepsi a check for the balance.

Pepsi rejected the order and returned the check. Leonard disagreed and took the company to court. In 1999, the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York sided with Pepsi, noting that no reasonable viewer would see the commercial as a genuine offer.

The ruling was later affirmed, and the case settled into marketing legend.

“No objective person could reasonably have concluded that the commercial actually offered a Harrier Jet.” – Judge Kimba Wood

Pepsi walked away unscathed, but the episode carved out a durable truth. When brands play with numbers, customers examine them closely.

Pepsi escaped because the jet was never on the table. Other companies have learned that the marketplace is not always so forgiving.

The Hoover Free Flights Fiasco

Some promotions unwind so completely that they shake the foundation of the brand behind them. Hoover’s free flights offer from 1992 has earned a reputation as the worst sales promotion in history.

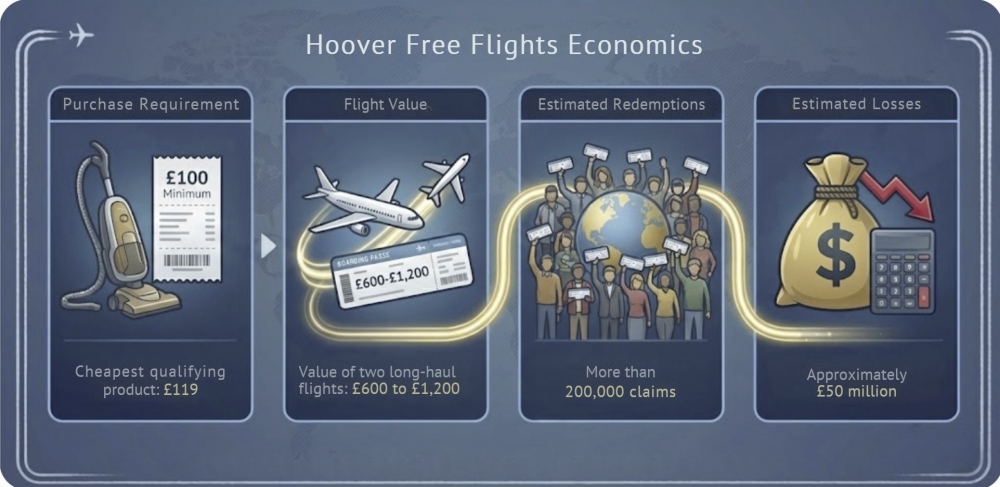

Hoover UK promised two free round-trip plane tickets with any purchase over 100 pounds. The cheapest qualifying vacuum cost 119 pounds. The flights were worth several times that amount. Shoppers immediately recognized the opportunity: buy a modest appliance, get hundreds of pounds worth of free travel.

Inside Hoover, the expectation was very different. Executives assumed customers would skim past the redemption process or lose steam midway through. Instead, more than 200,000 people claimed their tickets. The company became responsible for flights that dwarfed the revenue generated from the promotion.

Reports put Hoover’s losses near 50 million pounds. The fallout included executive dismissals, customer anger, legal battles, and ultimately the sale of the company’s European division to Candy. What began as a sales booster became a structural crisis.

The episode remains a classic example of promotional mispricing. Customers behaved logically, not aspirationally. They took the best value available, while the company clung to assumptions that collapsed on contact with reality.

McDonald’s 1984 Olympic Overspend

Promotions are often built on past performance, but past performance is no guarantee of future results. McDonald’s learned that lesson during its 1984 Olympics promotion, a case study in how the world can shift.

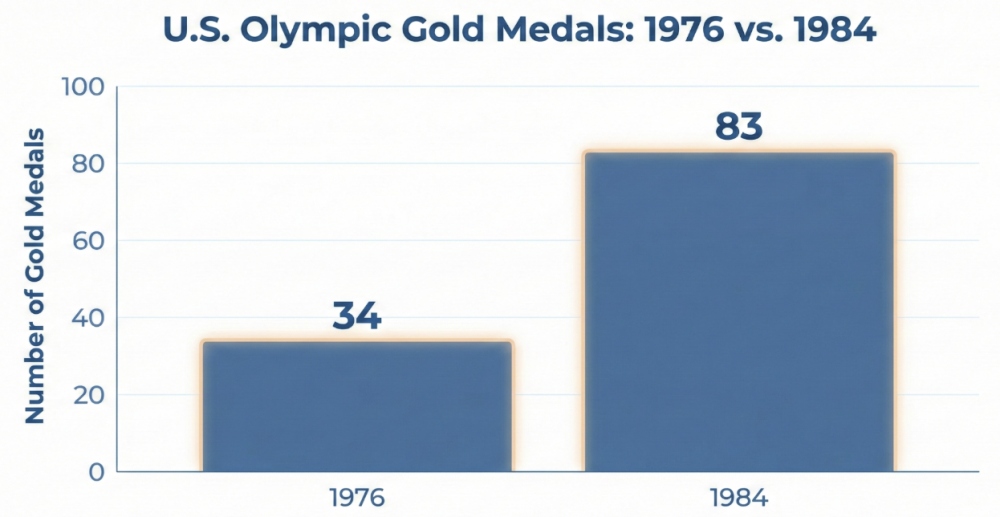

The company rolled out a scratch-card giveaway called “When the U.S. Wins, You Win.” Each card featured an Olympic event, and if the United States earned gold in that event, the customer received a free Big Mac. The projections came from the 1976 Olympics, when the U.S. brought home 34 gold medals.

Then the world changed. The Soviet Bloc boycotted the 1984 Los Angeles Games, which removed many of the strongest contenders. With the field wide open, the United States racked up 83 gold medals, more than twice the number McDonald’s had modeled.

Restaurants ran out of Big Macs. Costs ballooned. The company never published the total financial hit, but spokespersons later described it as one of the most expensive promotions in McDonald’s history.

The moment became cultural shorthand after its parody in a 1992 episode of The Simpsons, which highlighted how badly the math had been upended. McDonald’s had followed the data available at the time, but models only work when the world behaves predictably.

Red Lobster’s Endless Crab Disaster

Some promotions work too well, falling apart because customers embrace them with far more enthusiasm than the brand ever imagined. Red Lobster learned this in 2003 when it introduced its “Endless Snow Crab” special for $22.99.

Executives expected a reasonable dining pattern. The internal estimate was roughly three plates per guest. Many diners interpreted the offer differently. They settled in for long meals and kept the crab legs coming. At the same time, wholesale crab prices were rising, which knocked the economics further out of alignment.

The financial impact arrived quickly. Red Lobster recorded a $3.3 million loss in a single quarter. The parent company’s stock value fell by more than $400 million, and the division’s president stepped down soon after. One executive later summed it up neatly by saying that the third helping caused the damage, and the fourth and fifth helpings delivered the real pain.

Customers saw high value. The company saw unsustainable consumption. The gap created a multimillion-dollar loss.

The larger truth is that promotions cannot rely on the behavior a company hopes to see. They need to account for the full range of behavior customers might actually choose.

The $250,000 American Airlines Pass: A $21 Million Liability

Unlimited offers tend to attract the people most determined to get their money’s worth. American Airlines discovered that reality after launching the AAirpass in 1981. The company needed fast capital, so it introduced a lifetime first-class pass for $250,000, positioning it as a premium shortcut through a tough financial stretch.

Some buyers treated the pass as a standing invitation to fly whenever they pleased. One of the most cited examples is Steven Rothstein, who reportedly logged more than 10 million miles across more than 10,000 flights. Analysts estimate that his travel alone may have cost the airline as much as $21 million in flights, lounge access, and related services.

He was not the only enthusiast. Other passholders adopted similarly ambitious travel habits. A short-term revenue boost turned into a long-term liability. The airline ultimately revoked several passes, which led to legal disputes and settlements.

The AAirpass story shows how quickly an uncapped offer can tilt out of balance. The upfront cash looked helpful in the moment, but the long-term cost eclipsed that benefit. Unlimited programs are only sustainable when limits exist behind the scenes.

Marketer Takeaways

Promotional blowups can look unpredictable, yet the same patterns appear again and again. Those patterns offer practical guidance for any brand planning a high-value offer and hoping to keep it on the rails.

- Expect worst-case scenarios. Build projections around the highest possible redemption levels.

- Understand customer motivations. Assume people will chase the strongest value and try every angle your offer allows.

- Include limits and caps. Use ceilings, time windows, or qualification rules to keep enthusiasm from turning into exposure.

- Consider external variables. Any shifts in the market should ensure the math holds up under pressure.

- Never underestimate a savvy shopper. Expect every customer will stretch a dollar to its max.

Media Shower’s AI marketing platform helps you create promotions that buzz, not backfire. Click here for a free trial.

FAQ

What was the Pepsi Points Harrier jet case?

It was a legal dispute in which John Leonard attempted to redeem seven million Pepsi Points for a Harrier jet shown in a Pepsi commercial. The courts ruled that the ad was not a real offer.

What is the worst sales promotion in history?

Many analysts cite the Hoover free flights fiasco of 1992, which cost approximately 50 million pounds and contributed to the sale of the company’s European division.

Why do marketing promotions backfire?

Promotions fail when companies underestimate customer behavior, miscalculate costs, ignore outside variables, or leave loopholes in their terms.

How can marketers avoid promotional disasters?

Marketers can stress-test scenarios, add limits, assess real-world behavior, and build models that include the highest-risk outcomes.

How much did McDonald’s lose on its 1984 Olympics promotion?

McDonald’s did not release an official figure, but contemporaneous reports and corporate commentary indicate it was one of the costliest promotions in company history.