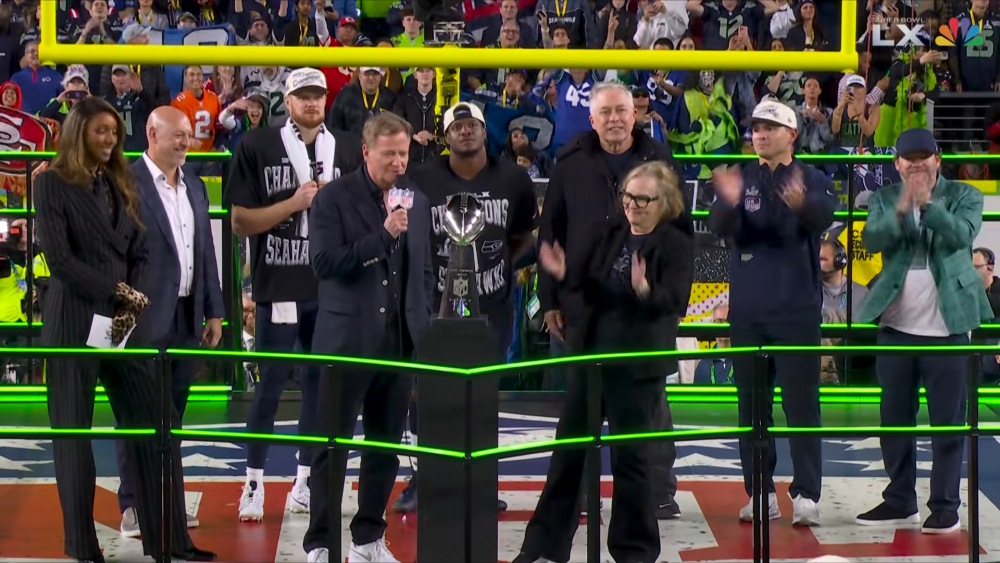

Super Bowl XL is behind us, and the Seattle Seahawks are the reigning world champs. The classic East-West matchup between the New England Patriots and the Seahawks is also a fascinating case study in brand power involving two franchises with some of the most disciplined brand identities and devoted fan bases in all of sports.

The Seahawk’s brand story really begins in 2005, when the New York Giants stepped onto the turf at Lumen Field. They were a team of giants in both name and stature, led by a young Eli Manning and a coaching staff that prided itself on clinical execution.

But as they approached the line of scrimmage for their first drive, the air began to vibrate. The noise was a physical pressure, an acoustic weight that made it impossible for the offensive linemen to hear the man standing six inches to their left.

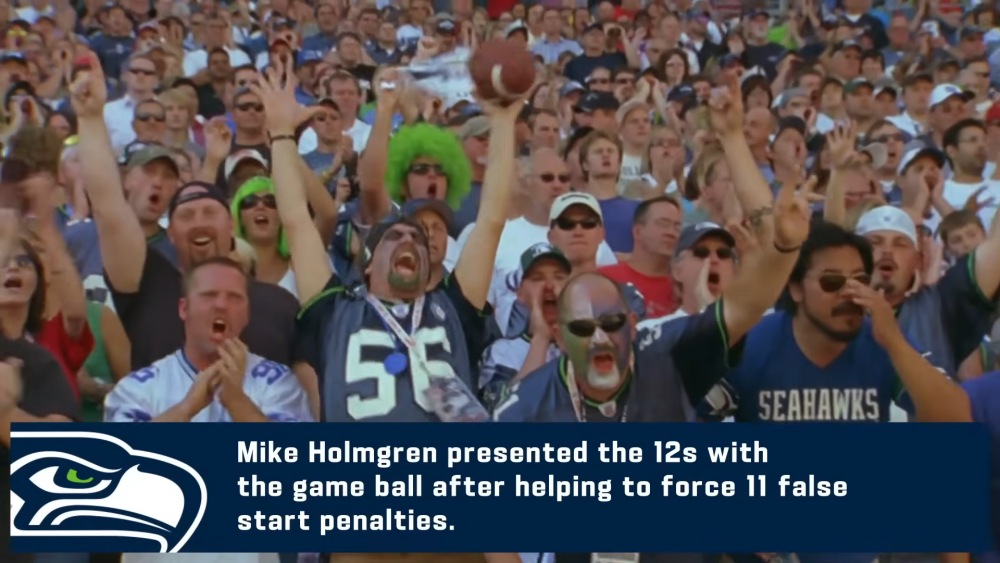

By the end of the game, the Giants had committed 11 false start penalties. Their kicker, Jay Feely, who had missed only two kicks all year, missed three potential game-winners in a row.

The Giants were systematically dismantled by a group of people who weren’t even on the payroll.

The Seahawks built their brand around this not-so-secret weapon. The fans built the advantage, but the franchise had the discipline to get out of the way.

They shifted their fans from spectators into “owners” and let that shared identity drive loyalty and competitive advantage.

The Concrete Cauldron

The story begins long before the ludicrous 2005 “Penalty Bowl,” back in the brutalist era of the 1980s. The Seahawks played in the Kingdome, a concrete multipurpose stadium that looked more like a grain silo than a sports cathedral.

It was bleak, but it had a secret weapon: a concrete roof that acted as a perfect acoustic reflector.

During the mid-80s, the fans, unprompted, began to realize their collective power. Their cheering became disruption that forced timeouts and became a tactical variable. Opposing quarterbacks complained to the media that Seattle had an unfair advantage, as if there were an extra man on the field helping the defense.

The 12th Man

The organization saw an opportunity to turn this “extra man” myth into a brand reality, and the 12th man was born. To show their gratitude to the fans, the “12th man,” they retired the number 12 jersey in 1984.

Guidelines are a little looser now, but in the ‘80s, retiring a jersey was an honor reserved for legends — Hall of Fame players who had given their blood and sweat to the franchise. By giving that specific number to the fans, symbolizing a twelfth player on an eleven-man unit, the Seahawks fundamentally changed the contract to give the fans ownership in the brand.

In effect, they gave the person in Section 322 a deed to the franchise.

Lumen Field and the Science of Loud

When the Kingdome was scheduled for demolition in the late ‘90s, the team’s future in Seattle was uncertain. When Paul Allen purchased the franchise, his vision for a new stadium was focused on one strange, specific request: Make it even louder than the last one.

Lumen Field, opened in 2002, is a masterpiece of intentional acoustics. The stadium features two massive, sweeping roof canopies that cover most of the seating. While they provide shelter from the legendary Seattle rain, their true purpose is found in their shape.

The canopies are parabolic reflectors. When a fan in the upper deck screams, that sound hits the canopy and is channeled directly down onto the field.

The stadium was also built on a remarkably tight footprint, with seats closer to the sidelines than almost any other venue in the league. This created a “cauldron” effect where energy couldn’t escape. It could only circulate and intensify.

To add to the effect, the franchise made the 3000-seat bleachers in the north end zone out of aluminum. When fans stomp on these metal planks, it creates a percussive sound that resonates at low frequencies.

The Seahawks built their fans a massive megaphone and invited them to use it.

Hawk Hill: The Brand’s Acoustic Engine

While the stadium’s architecture provides the acoustics, the North End Zone bleachers, known as “Hawk Hill,” provide the raw energy. This is a self-governed territory of the team’s most dedicated advocates.

Together, the Seahawks’ human-architectural synergy might well be the biggest home field advantage in sports history.

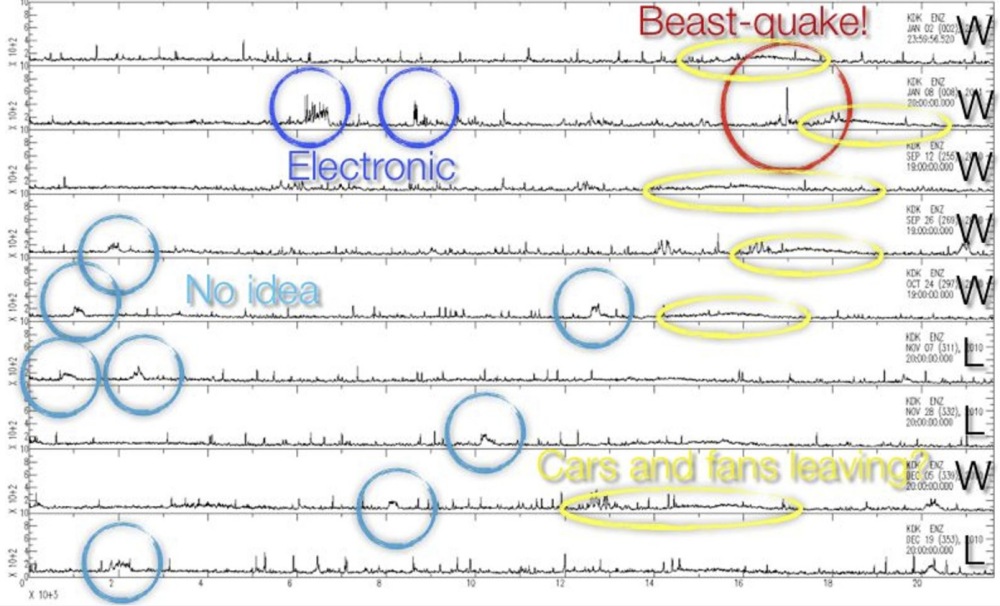

Case in point: On January 8, 2011, the 7-9 Seahawks were double-digit underdogs against the defending Super Bowl champion New Orleans Saints. Late in the fourth quarter, Marshawn Lynch broke through nine tackles for a 67-yard touchdown run.

As he crossed the goal line, the noise was so concentrated, and the rhythmic jumping of the crowd was so synchronized, that a nearby seismograph station at the University of Washington recorded a magnitude 1 to 2 seismic event.

From a brand perspective, the customers were so invested in the product that they moved the tectonic plates beneath the city. Fans were fueling the plays with their own kinetic energy as physical participants in the team’s success.

The Rule of 12s

As the “12th Man” brand grew into a national phenomenon, it hit a snag. Texas A&M University had trademarked the term “12th Man” in 1990. For years, the Seahawks had paid a licensing fee to the university to use the name.

It worked, but it always felt like living in a rented house.

“Earthquates are not predictable, but Seahawk fan enthusiasm is . . . . The “Beast Quake” of Jan. 8, 2011 indicated to us that Seattle Seahawk fans can really rock the world.” – Pacific Northwest Seismic Network

As the team surged toward their first Super Bowl victory in 2013 (notably 12 years ago), the community began to shift. On social media and in local bars, fans started referring to themselves simply as ”The 12s.” The Seahawks’ front office had a choice: spend millions in legal fees to defend a borrowed trademark, or listen to the shorthand their “fan owners” were already using.

They went with the fans. They replaced the old “12th Man” signage with simple but massive “12” flags. With that move, the team gained total brand autonomy. While other sports brands belonged to corporate headquarters, the identity of the Seahawks belonged to the people wearing the jerseys in Seattle.

Blue Friday

During the legendary 2013–2014 championship run, the brand identity spilled out of the stadium and into the streets. If you walk through downtown Seattle on a Friday during football season, you’ll see the city change color.

Skyscrapers, buses, baristas, and CEOs all wear the same navy and neon green.

This is “Blue Friday,” a ritual that gives Seattleites a way to signal their membership in the community. It transforms the city’s population into a living extension of the team’s infrastructure, and everyone is an active stakeholder.

This shared identity is a powerful competitive moat; once a customer is woven into the social fabric of the city, the cost of switching to a rival brand becomes unthinkable.

Going Global . . .

The Seahawks have successfully exported their brand far beyond the Pacific Northwest. In 2022, when the NFL played its first regular-season game in Germany, the stadium in Munich was a sea of “12” flags. The franchise made it happen by exporting portable rituals.

Actions like the raising of the 12 flag could be replicated at a pub in Hamburg just as easily as in Seattle.

. . . and Digital

The identity has moved into the digital world as well. Even their data collection is fans-first. The Seahawks use it not to sell more, but to know more. They recognize a 30-year season-ticket holder differently than a newcomer. When a fan logs into the team app, they are treated with the respect a long-term stakeholder deserves.

It’s the difference between being a user and being an owner.

How Brands Become Movements

The psychology of the “12s” transcends football. At its root, it’s about the human desire to belong. Some of the most successful brands have recognized this and run with the blueprint.

- HubSpot. Walk into any marketing department and you’ll find HubSpot disciples—a community built on the codified “Inbound” philosophy. They turned customers into teammates.

- Salesforce. Salesforce did the same with its “Trailblazer” community, giving users an identity and a hierarchy of badges. When someone puts “Trailblazer” in their LinkedIn headline, they have claimed ownership of that identity to further their careers.

- Harley-Davidson. Even Harley-Davidson mastered this decades ago by providing the “stadium” (rallies) and the “jersey” (leather vests), then stepping back and letting the community lead the way.

In all these cases, the brand stopped being a product and became a badge of membership.

“12 is not my number. It’s our number now.” – Sam Adkins, the only player who has ever worn the 12 for Seattle.

The Ownership Advantage

The success of the Seahawks model shows that the most resilient brands don’t just happen. By handing over the deed to the identity, the franchise transformed a three-hour game into a permanent, city-wide asset.

When your customers start doing the heavy lifting, whether they’re shaking a stadium or defending your software on Reddit, the brand is no longer yours to manage. It belongs to the people who showed up to play.

Marketer’s Takeaways

- Give your audience a job. People value what they help build.

- Build for the outcome. Your infrastructure, physical or digital, should be an instrument for your brand’s core strength.

- Listen for nicknames: Brands are built in the wild. When your community starts using their own slang (like “The 12s”) for your product, adopt it.

- Scale through ritual: Rituals like Blue Friday are portable. Build simple, repeatable actions that signal “I belong here.”

- Reward the tenure: Use data to treat your long-term advocates like the VIPs they are.

- Get out of the way: The strongest brands are the ones that give up the most control. Provide the platform, set the stage, and let your customers lead the chant.

In case you missed it: We also profiled the New England Patriots, another franchise with a powerful branding story. Read it here.