Quick Summary

- The anti-auteur approach. Rob Reiner built one of Hollywood’s most remarkable directing careers by refusing to make himself the center of attention. He prioritized human connection.

- Substance over spectacle. While contemporaries chased visual signatures, Reiner let dialogue, character, and emotional truth do the work.

- Collaboration as strategy. His “serve the master” philosophy turned every film into a team effort where ego took a backseat to excellence.

- Sincerity wins. In an era of increasing cynicism, Reiner’s earnest approach to storytelling created films that endure decades later.

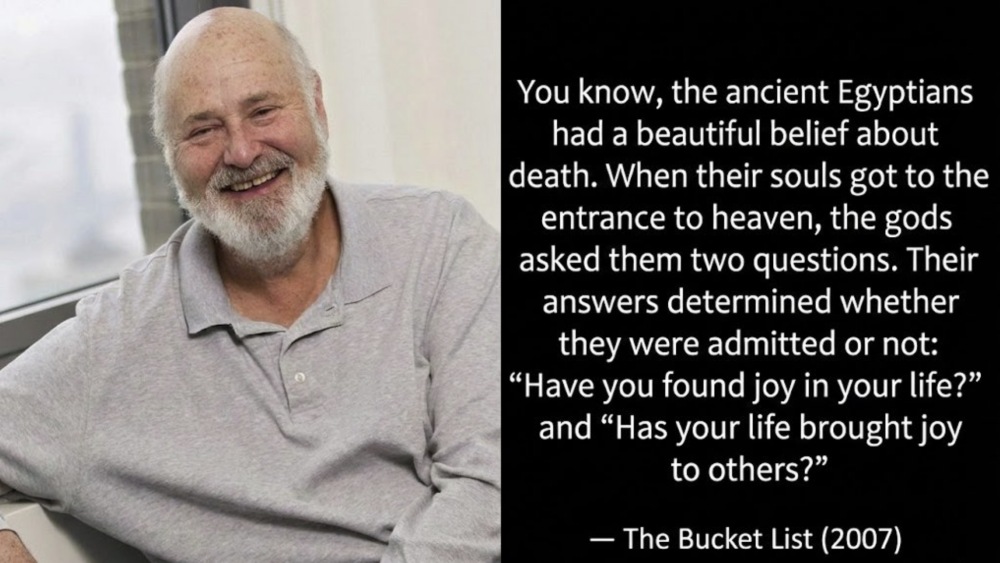

Perhaps Rob Reiner’s greatest skill was knowing when to get out of the way.

His list of blockbuster hits is legendary: This Is Spinal Tap, The Princess Bride, Stand by Me, When Harry Met Sally, Misery, A Few Good Men. His films grossed over $1 billion worldwide. Critics praised his “effortless” style. Actors described feeling “safe” under his direction.

Reiner mastered something most brands struggle with: making the message matter more than the messenger. Marketers should take notes.

While Spielberg crafted signature crane shots and Scorsese built visceral intensity through camera movement, Reiner simply pointed his lens at people being human, and created enduring works of art.

From Meathead to Master Communicator

Before Reiner directed anything, he was America’s favorite liberal son-in-law. As Michael “Meathead” Stivic on All in the Family, he spent nine years delivering Norman Lear’s socially conscious scripts to 50 million Americans each week.

Those nine seasons became his graduate education in communication.

All in the Family taught Reiner how arguments actually work, how families really talk, and how to land emotional beats that resonated across the political spectrum.

More importantly, it showed him what actors need: safety, trust, and directors who don’t need to prove they’re the smartest person in the room.

That experience shaped everything that followed.

The Reiner Method: Invisible Excellence

Restraint as power

Reiner’s communication genius lay in what he didn’t do: He didn’t move the camera around unnecessarily. He didn’t light scenes to show off his technical knowledge. He didn’t insert directorial flourishes that announced “A Rob Reiner Film.”

Film critics called it an “invisible style,” which sounds like a backhanded compliment until you realize it’s the hardest thing to pull off. Making something look effortless requires extraordinary control. Hawks had it, Ford had it, and Reiner had it.

When Steven Spielberg moves his camera, you feel wonder. When Scorsese cuts, you feel energy. When Reiner frames a shot, you just feel the characters … and that’s the point.

Characters over concepts

Even This Is Spinal Tap, a mockumentary about the world’s dumbest band, worked because Reiner never mocked his characters. He observed how pride, insecurity, and dreams collide when you’re convinced your amplifier goes to 11. The humor landed because the emotion was real.

This empathetic lens worked across genres. Audiences felt the coming-of-age ache in Stand by Me, the will-they-won’t-they tension in When Harry Met Sally, and the courtroom intensity in A Few Good Men. Different stories, but they shared a foundation: deeply human characters experiencing authentic emotions.

“I’ve tried to make films that are about real people going through real situations. Most of the films are about human beings experiencing things that we all experience.” – Rob Reiner

Sincerity in a cynical age

By the late 1980s, Hollywood was falling in love with ironic detachment. Quentin Tarantino was around the corner, and postmodern self-awareness was becoming the default mode.

Reiner stayed the course.

He believed audiences could feel deeply without embarrassment, and he designed his films to prove it. Even Spinal Tap, which could have been cruel, showed genuine affection for its characters. It has endured for 40 years because the band’s absurdity can’t be separated from their sincerity.

When Meg Ryan fakes an orgasm in a crowded deli, Reiner’s camera doesn’t wink (or blink). When Billy Crystal realizes he’s in love, the moment plays straight without ironic distance of hedging.

In a marketing landscape drowning in brands that constantly nudge-nudge-wink-wink at their audiences, Reiner’s earnestness feels revolutionary.

Strategy in Action: The Films That Made the Method

“This Is Spinal Tap”: Observation without ego

Reiner’s directorial debut showed his entire philosophy in 82 minutes. By playing the documentarian Marty DiBergi (a mashup of Scorsese, De Palma, Bergman, and Fellini), he put himself in the film, then made himself invisible.

The mockumentary format let him observe musicians’ delusions without cruelty. When guitarist Nigel Tufnel explains that his amp goes to 11 because “it’s one louder,” Reiner trusted that the audience didn’t need reaction shots or editorial commentary to tell us it was funny.

That trust became a Reiner trademark. He consistently gave viewers credit for noticing small details rather than underlining every joke or emotional beat.

The film made $4.7 million on a $2.25 million budget and launched a new genre. More importantly, it established Reiner as a director who understood that great communication means knowing when to shut up.

The legendary “goes to 11” scene.

“The Princess Bride”: Tone control as a superpower

Arguably Reiner’s most beloved film, The Princess Bride almost didn’t get made. Many filmmakers considered it, but because it was impossible to capture in a single genre, none ever knew quite what to do with it.

The Princess Bride works because it treats sincerity as the joke—and then refuses to break it. On the surface, it’s a fairy tale assembled from familiar parts: a farm boy, a princess, sword fights, giants, and true love. Underneath, it’s a precise exercise in tone control.

The film knows exactly how absurd its premise is, but it never mocks the emotions at the center of the story.

Again, the film’s brilliance lies in its restraint. The humor comes from character behavior and timing, not from undercutting the stakes. Inigo’s grief, Westley’s devotion, and Buttercup’s confusion are all played straight.

Because the film believes in its characters, the audience does too. The result is a story that feels light without being hollow and nostalgic without being cynical.

“When Harry Met Sally”: Letting brilliance breathe

Reiner’s collaboration with Nora Ephron produced what may be the finest romantic comedy of its era. The movie showed what happens when a director serves the script rather than competing with it.

Ephron’s dialogue was exquisite and Reiner’s direction was almost imperceptible. No showy camera work distracted from two people gradually realizing they’re meant for each other.

The famous diner scene demonstrates his approach perfectly: simple coverage of reactions without cutaways or fancy editing. The communication lives in Meg Ryan’s performance and the surrounding diners’ responses, not in directorial pyrotechnics calling attention to themselves.

The film earned $92.8 million domestically (on a $16 million budget) and gave us lines people still quote 35 years later. “I’ll have what she’s having” (spoken by Reiner’s real-life mother) entered the cultural lexicon.

“A Few Good Men”: Collaboration at full throttle

Working with first-time screenwriter Aaron Sorkin, Reiner became the collaborative partner every writer dreams of (and initially fears).

Sorkin later recalled Reiner calling at all hours with ideas, diving so deep into the script that he essentially wrote the final draft himself. But he never claimed ownership.

“If everybody understands the process is collaborative and there is no ownership on it, then you get in there and do whatever it takes.”

The courtroom climax—”You can’t handle the truth!”—shows Reiner at his directorial peak: confident coverage that lets Jack Nicholson’s performance and Sorkin’s words create the electricity.

The film earned $243 million worldwide and launched Sorkin’s screenwriting career. It was no coincidence that Reiner’s primary goal was making everyone else look brilliant.

“Misery:” Restraint turned claustrophobic

The film strips storytelling down to its most brutal power dynamic: the creator and the audience. A writer is immobilized, and a reader decides his fate. Reiner directs Misery with the same invisible discipline he applies to comedy, but here that restraint becomes suffocating.

The camera stays close, and the setting never expands. Dialogue does the damage.

Annie Wilkes is terrifying not because she’s chaotic, but because she’s convinced she’s right. Her violence is rooted in devotion. She loves the story too much to let it change.

The film doubles as a quiet meditation on authorship and expectation. Paul Sheldon is punished not for bad writing but for evolving. The tension between creative growth and audience control is what gives Misery its lasting power.

Reiner never sensationalizes the horror. He trusts the material to do the work. Because of that trust, the fear feels disturbingly plausible.

The Culture That Made Reiner’s Style Revolutionary

Understanding why Reiner’s approach mattered requires understanding what was happening in 1980s-90s Hollywood.

The auteur theory was imported from France in the 1960s. It was the philosophy that directors were the true “authors” of films.

By the 1980s, that meant visual signatures became everything. Spielberg’s lens flares and de Palma’s split diopter shots are good examples, as are Scorsese’s tracking shots through the Copacabana.

These techniques were brilliant, but they were about showing off.

Reiner came up during this era, but he had a different vision. He’d grown up watching his father and the comedy writers of the 1950s, where the joke mattered more than who told it.

He’d spent nine years on All in the Family, where Norman Lear’s social commentary worked because it felt like real family conversations.

So while his contemporaries were announcing their artistic vision with every frame, Reiner was erasing his fingerprints. The film was the master that everyone, including the director, served faithfully.

Only a director completely secure in his abilities could make strategic restraint look this easy.

What Reiner Knew About Human Connection

Multiple journalists described similar experiences interviewing Reiner. Before diving into questions about Spinal Tap or The Princess Bride, he’d pause to ask about their fathers’ careers. He’d interrupt to take calls from his wife Michele. He’d make actual human connections.

It all reflected his fundamental belief: Communication works best when you actually care about the people you’re communicating with.

That philosophy extended to every collaborator. He recognized that the “quality of the pen clearly matters” and created conditions for writers to thrive.

Actors consistently described feeling “safe” with Reiner. He trusted them to deliver their best work without ego or intimidation. That trust produced some of the most memorable performances of the time.

Reiner understood that great communication didn’t mean proving you’re smart. It’s about making everyone else feel smart enough to contribute their best.

The Lasting Impact

Rob Reiner directed 24 feature films. Many of them became cultural touchstones that people quote decades later. His work grossed over $1 billion worldwide.

But the deeper legacy is his approach, showing that great communication requires not flash but clarity, empathy, and commitment to “story truth.”

In an age of attention-grabbing marketing stunts and viral gimmicks, Reiner’s approach feels almost radical: What if we just made something good? What if we trusted our audience? What if we let the substance speak for itself?

His films remain quotable because they captured authentic human experiences with warmth and sincerity. They asked audiences to slow down, look closer, listen, and care, then rewarded that attention with emotional truth.

For marketers navigating an increasingly noisy landscape, Reiner’s career suggests a different path forward: Less flash, more substance. Less cleverness, more empathy. Less ego, more collaboration.

Trust your message. Serve your audience. Make it human. The rest takes care of itself.

Marketer Takeaways

- Make substance the star. Strong ideas don’t need to announce their cleverness. When the message is real, technique should support it, not compete with it.

- Write for humans, not personas. Reiner focused on people with real emotions, not demographic buckets. Empathy beats segmentation every time.

- Choose sincerity strategically. Earnest communication cuts through cynicism. Audiences trust brands that mean what they say.

- Serve the work, not your ego. The goal is the best possible outcome, not the smartest-looking solution. Collaboration beats control.

- Master conventions, then bend them. Reiner understood genre rules before breaking them. Fluency creates room for innovation.

- Observe, don’t judge. Lasting work comes from understanding real motivations, not mocking them. Curiosity outperforms assumptions.

- Invest in exceptional writing. Great ideas live or die on the page. Strong writing can’t be replaced by production tricks.

- Create safety for excellence. Teams do their best work when risk-taking feels supported. Psychological safety fuels creativity.

- Keep it simple. Save energy for decisions that matter. Strategy beats overthinking execution.

Media Shower’s AI marketing platform helps you create campaigns that get it right on the first take. Click here for a free trial.